Backwards and Forwards

On Thursday I traveled to Taichung to visit the two historians who presented their in-progress book on the history of the Tamsui River at the Taiwan Water Agency Office meeting a few weeks ago. A married couple and research team, Dr. Ku Yawen and Dr. Li Zongxin picked me up at the station. We had lunch at a vegetarian cafe in the mountain outside Taichung city and then went to a nearby cafe to talk. Our conversation was wide-ranging and facilitated partly by the sometimes ambiguous support of Google Translate. Through it, a few threads stood out to me. I’ve sketched two of them below, roughly, pocked with missing information and potential inaccuracies, from my messy notes capturing a half-fluent conversation had over coffee and the ruffle of archival reproductions.

Shezidao Again

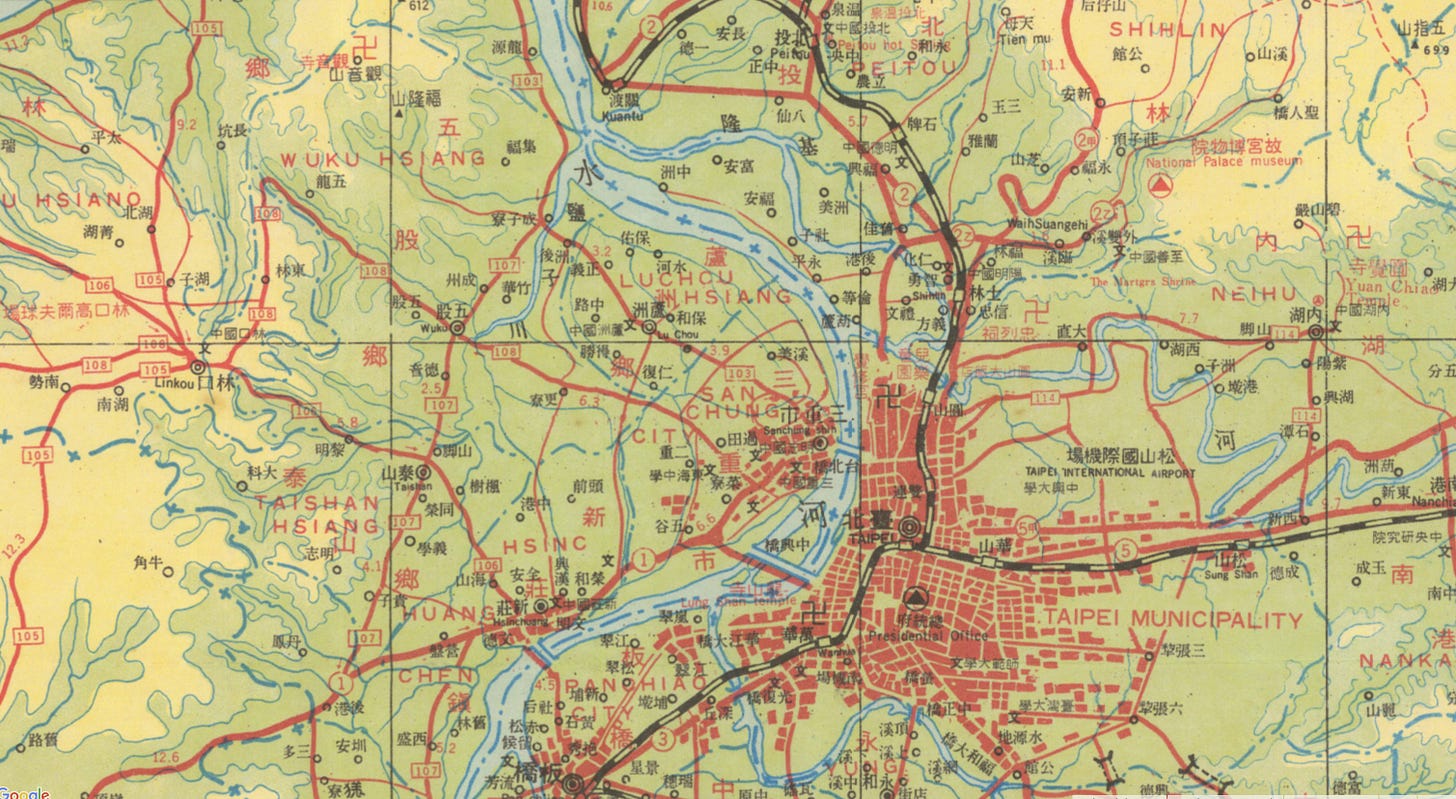

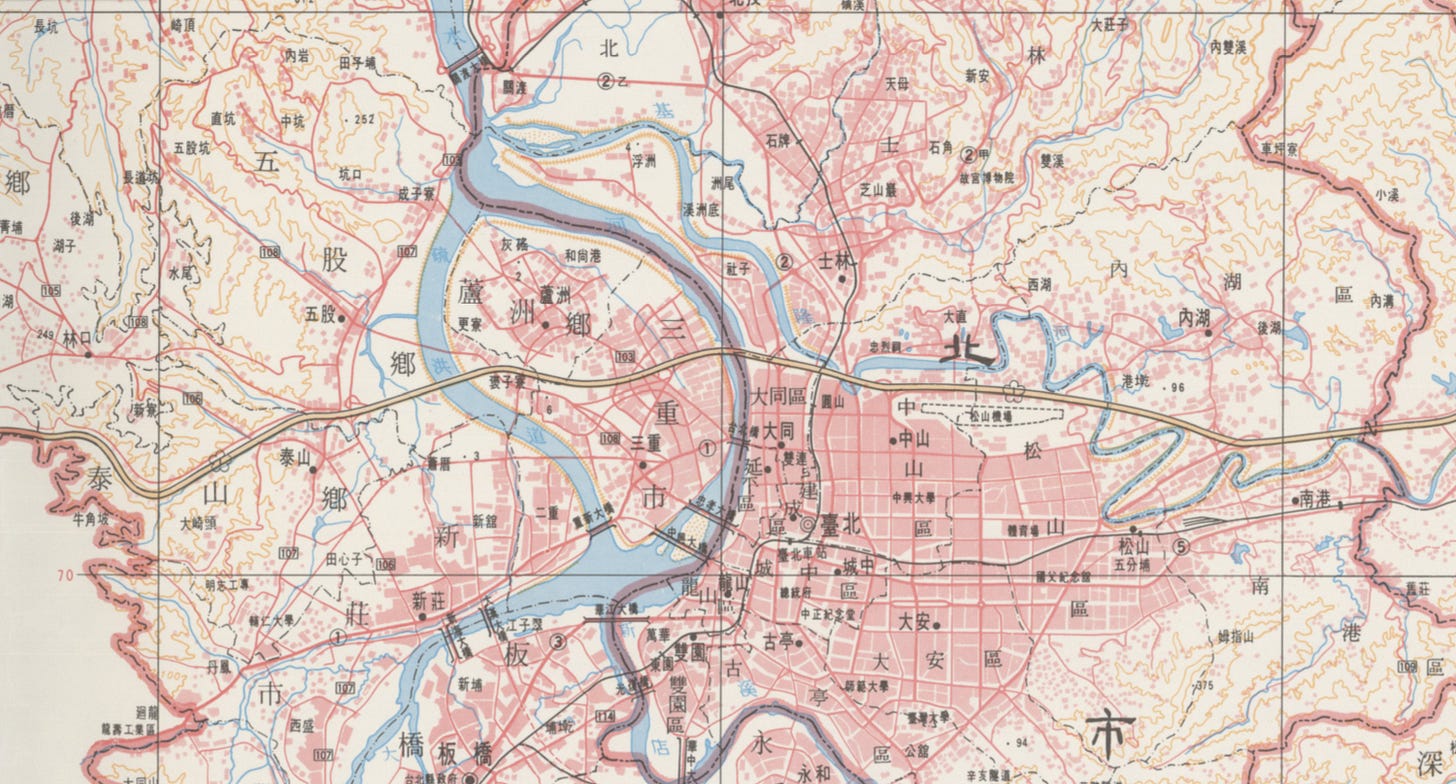

Before Japanese colonization in 1895, farmers in Shezidao had a unique way of managing the flooding that frequently inundated their land. Rather than attempting to reduce flooding, they managed the impacts through distributing risk. Shezidao was divided into rotating plots with tenures of around five years, so that no one single farmer would be flooded again and again. Embankments and other early flood control infrastructure were built collectively. When the Japanese arrived, they struggled to understand this structure of property “ownership.” For the purposes of colonization and the standardization that comes with it, they attempted to draw a map of the lot pattern to assign ownership. As Dr. Ku described this to me, I imagined a grid of lines dividing land into neat squares, but later she showed me a picture of the map that the Japanese colonists had drawn. The plots were amorphous shapes, differing in size and orientation, each a different shade of watercolor. Naturally, understandings of risk and farming potential were multivariable and dependent on topography: a small plot on high ground may very well be “worth” more that the swath of land that hugs the riverbank.

7 Methods of flood control as devised by the colonial Japanese government some time in the early 1900s:

The Japanese government understood the need to combat flooding in Taipei. They put forth a list of seven methods for flood control. Most were scrapped at the time due to cost and logistical complexity. They include:

Dredging

Widening the river

Building a waterway off the Dahan River that would connect it to the Tamsui further downstream and reduce the flow bottleneck at the confluence of the Dahan River and the Xindian River. A version of this actually happened several decades later with the construction of the Erchong Floodway (more on that in coming posts…)

Protecting and amplifying forest cover and soil health to reduce erosion (quite avant-garde, no?)

Building a reservoir upstream (a version of this also happened later)…

Building a flood wall completely encircling Taipei

Building embankments. This is the one they settled on, creating an ambitious Taipei-scale plan and starting construction with an embankment at Dadaocheng. They were only able to complete 10% of this plan while in power but the use of embankments was solidified as a relatively effective method for flood control that proliferated through Taipei in the coming decades.

The beginning of a research project is confusing, full of open expanses of blank paper, irrelevant background research, unhealthy skepticism, dead ends and deadlines… But every now and then there are sparks, moments of “that’s interesting!,” sudden accelerations. The allure of the unexpected is a structuring force. Each of these threads becomes a mandate for further inquiry, a prompt that drives the next phase searching for specifics and evidence. One conversation can provide just enough cracks in the wall to realize there’s a world on the other side.

Heavy Sun

I took a bike ride from Yuanshan Farmer’s Market around Shezidao and back to Dadaocheng.

I bicycled beneath an overpass so full of birds that the sound was overwhelming. It was impossible to hear anything else but just as hard to see the source of the sound. There were no great flocks clouding the sky, only their sound and the white hot sun. A man stood under the overpass yelling into his phone over the din. Why would you make a phone call here? There was something almost cartoonish about it.

At times the heat was mind-altering, like wading through light. My sunglasses slipped down my nose, I felt my skin crackle. When I got back to the apartment, a nausea descended as the air conditioning rapidly lowered my internal body temperature. The weather app said the highs were similar to New York this summer but the heat was not New York heat.

American Girls

On Friday night I burst into my apartment and ran to the notebook on my desk. Reality fell into place like a formerly inscrutable game of tetris. I feverishly wrote, “The Iowa Writer’s Workshop? The formation of American individualism and identity? How do American Girl Dolls relate?”

Although I never had an American Girl Doll as a child, I couldn’t get it out of my head that the phenomena of the American Girl Doll was a project of shaping and naturalizing certain ideas about history and identity, much as the Iowa Writers Workshop solidified the psychological, first-person style as a hallmark of American literature (Matthew Salesses unpacks this in his book, Craft in the Real World). The hyper-capitalist political mood of Reagan-era policy enveloped the founding of American Girl and the release of the first three dolls in 1986. They were Molly (whose father is stationed in Europe in World War II), Kirsten (a Swedish immigrant to Minnesota in the 1800s), and Samantha (Victorian vibes).

The plot continues to thicken as American Girl Doll marched through the 90s and aughts embodied by choices about which moments of history to memorialize in doll-form, the role and rollout of different ethnic and cultural identities and the stories they’re wielded to tell, and the advent of Create-Your-Own dolls that could be customized to look like the girl who ordered one. The Create-Your-Own dolls were pointedly ahistorical, lacking the context and background that defined the other dolls.

American Girl Dolls were also always very expensive. In 1986, the doll and book set cost a steep $86. Today it costs $160. Accessories and add-ons racked up the price. Access to the American Girl story was inflected by class; history’s diminutive co-authors tugging on their mother’s sleeves at the checkout line.

The line between reflecting common values and norms and shaping them is difficult to see. Nonetheless, the American Girl Doll as a record of certain cultural and political leanings feels oddly relevant.

Last Sunday I visited The National Center of Photography and Images and found myself flipping through a photo book by Justine Kurland called Girl Pictures. The photographs are all constructed, staged. She writes poignantly about her process in the introductory text, describing how she devised scenes of runaways and vagabond girls in collaboration with her rebellious teenage subjects, all of whom seemed to embrace the chance to act out a scene in a life they had not actually lived. I was struck by how mutable and reciprocal the line between girls and dolls became, how youthful feminine identity could form an imaginary of constructed ideals defined as much by the observer as by the observed, how easy and difficult it is to play make believe.

In any case, I digress.